|

|  |

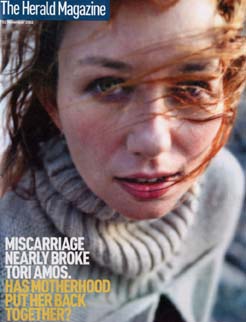

Tori was the cover story in the November 2, 2002 issue of The Herald Magazine, which is a Saturday insert in The Herald newspaper in Glasgow, U.K. Erin Gobel sent me the article and scans of some of the photos, which you can read and view below.

Click to see larger.

The Herald Newspaper's Saturday special called The Herald Magazine Glasgow, Scotland

2 November 2002

Cover Story

Words: Tom Doyle

Photograph: Ellis Parrinder

"I could get pregnant but I couldn't carry life. I was demoralised. Motherhood put everything into perspective." "I could get pregnant but I couldn't carry life. I was demoralised. Motherhood put everything into perspective."

Tori Amos says that if she could pick anyone - living or dead, possible or impossible - to play her in an imagined film biopic of her life, there could only really be one choice: the young Shirley MacLaine. It's easy to see how she would have been perfect. Both women share so many attributes: the fiery locks, the penetrating blue-green gaze, the otherworldly manner and unshakeable belief in the life beyond the physical world and the fact that they seem to be tuned to a different frequency from the rest of us, seemingly receiving messages beamed in from another dimension.

This is the typical image we have of Tori Amos: airy, absent, slightly unhinged, prone to rambling therapy-speak and psychobabble. In many ways, she reckons, these are the more spiritually-rooted characteristics that she inherited from her part-Cherokee mother. But there's another, lesser-spotted side to the 39-year-old North Carolina-born singer-song-writer which is more pragmatic, but unrelenting, feisty and fiercely determined. These are the generic traits for which, perhaps unsurprisingly, Amos thanks her Scottish Methodist minister father.

"Having a Scottish father . . . y'know, they can be as tough as old boots," she says, laughing, revealing rows of neat little canines and sharp incisors, her slight shoulders framed by a night-lit view of the Thames, five floors below through the window of her Aldwych hotel suite. "But as the years have gone on," she continues, "some days he can really be the only one that makes sense. Especially in times of trauma and tragedy and when things are at their worst because being Scottish, he is doom and gloom, but nothing can shock him. He's always there in the trenches, digging you out."

Nevertheless, her experience of an upbringing with a Scottish parent - who was brought up barefooted in the Deliverance country of the Appalachian mountains - didn't exactly help her to disprove certain, tighter-fisted aspects of the national stereotype. She still visibly cringes at the memory of being put through the humiliating ritual of standing in the supermarket queues with her father as he "weighed up the tomatoes until they were exactly 53 cents, not 54, and there was a whole line of people waiting behind him".

Still, she's keen to point out, the Reverend Edison Amos was nothing if not supportive of his prodigious daughter throughout her formative musical years. "When it became obvious that I was going to be a musician, I think there was a part of him that came alive."

Myra Ellen Amos (she changed her name to Tori at 17, figuring that anyone called Myra Ellen could provoke nothing more than a "limp dick" in potential boyfriends) first crawled up onto a piano stool at the staggering age of two-and-a-half. Her apparently instinctive talent as a pianist led to her becoming the youngest ever scholar of the Peabody Institute in Baltimore. But at 11 - more enamoured of Led Zeppelin than her classical studies - she was expelled, spectacularly exploding her father's dreams of having a concert pianist daughter.

This, it seems, was only the first of many instalments in which she was to prove a disappointment to her father. Even if, in her late teens, he was to dutifully fulfil the role of chaperone throughout her soul-destroying years of playing piano bar standards in hotel lounges and gay clubs, while mailing out endless demo cassettes to record labels ("He would've made a good agent, my dad"), Amos admits her father also had a frustrating tendency to raise the bar a little higher with his daughter's every achievement.

Attempt to scratch even the surface of Tori Amos's psyche and it's easy to see how this provided a source of motivation for her, but also, more indelibly, a deeper sense of hurt.

"It's that crazy thing about when things are good, it's never enough," she offers, openly. "That's what I grew up with. You win the talent competition in Montgomery County - it's never enough. 'You were nominated for how many Grammies? But you didn't win one, did you?' Whatever you do, it's never enough. So yeah, I'll be honest with you, that is my button . . ."

By default or design, there's always been a strong impulse within Tori Amos - the minister's daughter, remember - to show the wider world, whether by way of her moving depiction (in the song Me and a Gun) of being raped in her early twenties, or rolling around hallucinating in the Mexican dust as part of her mushroom-shaped "studies" with a shaman. Or recording in the Los Angeles house where the Manson Family slaughtered Sharon Tate. Or - perhaps even more disturbingly - having her photograph taken apparently suckling a piglet on her left breast.

I ask her, considering how provocative and brutally honest she has been in the past, if there's anything she's ever said or done that she now regrets. Her answer, is surprising, if unsurprisingly oblique, and involves recent arguments with those who subscribe to the growing trend towards anti-Americanism.

"You walk into a room and you get this kind of vile hating-everything-you-stand-for feeling from them," she fumes, softly. "So I suppose in some ways I've later regretted even trying to argue with these people. I'm one of the Americans going 'Look, we're at a crossroads. But if you look at all of us as George W, then, y'know . . . we could do that to you with Thatcher.' As Americans, we do have a lot to look at, there's no question, but at the same time, sometimes at moments when you're faced with people like that, you do think of the upside of America."

The current state of America is a topic uppermost in Amos's thoughts at the moment, not only for political reasons. Scarlet's Walk, her seventh album, is a "sonic novel" - or, to put it less fashionably, concept album - charting the journey of the title's fictional character from the west to east coasts of the US. It's a sprawling, ambitious work (18 tracks) that tackles everything from the LA porn industry and the slaughter of Native Americans in the Midwest to planes crashing in New York airspace.

The latter, in particular, was partly prompted by first-hand experience. On the morning of 9/11, Amos woke in an uptown Manhattan hotel room and switched on the television. Within the hour, she was on the streets.

"You walked down Fifth Avenue and you could smell the burning," she recalls, eyes widening in disbelief. "That's the thing that made you realise, this is not a Die Hard movie. Going out into the city and seeing the mass exodus of people fleeing New York. My tour manager was going, 'We've got a bus leaving, do you want to hop on?' And I said, 'No . . . I'm not leaving here.' It was just this idea that New York was bleeding. Being there made it very . . . concrete," she stresses. "Also you're not seduced by all the media because you have your own impression. You're seeing the thing happen. But maybe being there made it a clear decision for me to tour."

While other artists were quick to erase their travel plans, Amos - a self-confessed "road dog" - spent the months that followed criss-crossing the country in her tour bus. "I'd been getting e-mails from people saying 'Hey don't sit there and do nothing. Don't cancel because we need a place to go.' That's the thing - rock 'n' roll seems to be able to move when everything else is standing still, the trucks and buses roll. You get two drivers and you don't stop.

But as much as the singer is keen to fly the patriotic flag, hers is an outlook that is tempered with cold reality. "In the last six months in America, there's been a feeling of inner betrayal," she says, "particularly among people who might've been a bit more . . . idealistic about the government. So there's been a kind of crash of what to believe. Which is not a bad thing . . ."

Although of course characteristically prone of flights of poetic whimsy, Tori Amos has herself periodically fallen victim to the crash of what to believe, not least in her attempts to become a mother.

The last time I interviewed her four years ago, on the release of her fourth album, From The Choirgirl Motel {{Okay, I can't believe they got this wrong, it does actually say Motel and not Hotel!}}, was the first time she had publicly spoken about a recent miscarriage. Subsequently, she was to suffer a further two. Later, she was struck down by what she believed to be a bout of stomach flu, and she and her Lincolnshire-born recording engineer husband Mark Hawley were privately thrilled to discover that the symptoms were in fact the result of an unplanned pregnancy.

In September 2000, having managed to keep the matter a secret even from her record company, Amos gave birth to a daughter, Natashya Lorien. Given her past experiences, I ask her if motherhood has proved to be everything she expected it to be. "More," she replies. "It's more because I'm older and because I didn't have a fantasy of it. Having the three miscarriages, I crashed and I was demoralised about it. Y'know, my body couldn't function, couldn't carry life. I could get pregnant, but I couldn't carry life. So you just feel like a Death Star. Talk about a psychological battle. You get into this kind of rut. Those were dark months, sometimes years. But motherhood puts everything into perspective," she decides, brightening. "I'm Tash's mom and I'm there to do that and be a warm and fuzzy place."

Amos married Hawley in March 1998, in a medieval-themed woodland ceremony in West Wycombe that can only be described as Arthurian. The couple live together in a 300-year-old cottage in North Cornwall annexed by their studio, Martian Engineering (the scene or recording of Amos' last three albums) and neighbouring a dairy farm, that most days sends a pungent reek of dung wafting through this rural idyll.

It's one of three properties - the others being a rural farmhouse in Ireland and a quiet holiday home in a retirement community in Florida - that the couple flit between, though it's the one they spend most of their time in, and, as such, might be called their real home. Amos has settled well into Cornwall, she says, to the point where even the local butchers' association has put in a request to record their annual Christmas album at the studio.

"I'm a guest here, " she smiles, "and so I'm always on my best behaviour. My mother always told me, 'Better to be Miss Manners than Miss America.' I'm as comfortable living in Florida, but I spend most of my time here because my husband is cantankerous and pernickety and difficult. This is very much about the fact that he has to live in Britain. We spend a lot of time in America - more than most people would think - because I'm working there all the time and that's my bread and butter. But he's not that comfortable there."

So it's a Guy and Madonna thing? He'd rather be in Britain, she'd rather be in America . . . "Well, I don't know if it's a similar situation because . . . uh . . . I think I better stop that right there." She pauses and laughs, deciding not to speculate too openly on Mrs Richie's domestic affairs.

"I would never presume to say what anyone should do. I don't know the inner workings of England. When you're born in a place and you grow up there, it's instinctive, it's a creature to you. America is my habitat and I know it blindfolded. Here, I'm kind of an exotic animal. I'm making friends with the land and the stories and the people. They've let me into Cornwall, they treat me lovingly."

What does working in the studio with your husband actually come down to in real terms? Do you argue about mixes? Does it get personal? Do you get sick of the sight of each other? I mean, you're the boss, obviously . . .

"Yeah, but I don't like pulling rank. Because when you have to pull rank, that means it's gone a bit far. But at the same time . . . things fly sometimes. Sometimes you have a heated conversation. But we've worked hard about what's below the belt. I don't believe in personal attacks. I believe in dealing with - as I've gotten older especially - what's wrong. Sometimes it's, 'Well that was a really ratty thing to say.' And sometimes it's like, 'Hey, have you taken the birth control today, how's the hormones doing?' But privately, there's a sacred pact. If we're going to blow up, we go in the other room . . ."

One subject certain to stoke Tori Amos at the moment is the matter of pirated music file-sharing on the internet, the multi-billion dollar problem that's continuing to fox the record industry. As a case in point, she says, recently, within 24 hours of six-track samplers of Scarlet's Walk being issued to the media, the songs appeared on the web.

"I know who got 'em, just a few hundred people," she says. "So it was an inside-the-industry job. Sony had done a copyright protection software and my engineers laughed and said it didn't work. I didn't think it would happen within 24 hours. I thought I had three weeks on it. So I think because it happened like that, I said, 'okay, close ranks.'"

And so Amos presented her recording engineers with a perplexing conundrum: how to let the media hear the rest of the album, without risking it being bootlegged. The result is a handful of sealed Walkmans - with glued-in headphones - containing a CD of Scarlet's Walk, which members of the press are lent for a limited period to hear the album and then must return intact.

Before our interview today, an Epic Records publicist let me hear the album on one of these seemingly impenetrable devices. I now admit to Amos I couldn't resist having a go at the "open" button.

"Yeah, well it's not easy, is it?" she berates me, playfully. "If you try to open it, the CD is designed to crack in half. Somebody we know tried to open it and had to go to the hospital."

Do you think MP3-swapping on the net has actually dented your sales? "Sure. Music-swapping is just huge. They can tell how many hits you've had on the music-swapping networks and for me, it's a few million. I've always said to people, 'If you need to take the music, then take it for whatever reason. But then at a certain point, if you don't give back to it, you become a taker."

"Y'know, they're not giving us free petrol for our buses to come across and do shows," she goes on, her voice rising in passion. "D'you see what I mean? I think basically, it's internal, it's something within people. People feel they have a right to take. That's what you're dealing with - it's an entitlement. Y'know, wine-tasting is one thing, but it's me putting bottles of wine in my pocket. If you think that a vineyard makes good wine and you want it to continue making it and you like what it stands for because it doesn't have eight-year-old children picking the grapes, then you have to pay for it."

Surely though, I suggest, it's not so much of a problem that it's likely to bankrupt her in the near future. "Listen I have no sob story to give you. I'm lucky that I'm okay, but I have to be really clever. But, y'know, at a certain point, when do we as a generation say, 'What do we believe in?' So many people are, 'What can I get?' not 'What's my part? What do I need to give?'"

Luckily, Amos reasons, the majority of her fanbase are more understanding than most. "They do give back," she says. "Other artists have said to me, 'God, can I borrow your audience?' And I've said, 'You have to ask them . . . I can't rent them out.' For the most part, they don't take it for granted. They try to help each other out and trade seats for shows and stuff. It's more of an extended community, kind of more like The Grateful Dead had, in a way."

This winter, Amos sets out on another of her exhaustive, continent-straddling tours in support of Scarlet's Walk. Travelling with her, as usual, will be her 60-strong crew of technicians who - as is the nature of these things - have become an extended family to her over the years.

Perhaps her relationship with them, however, best serves to highlight the duality within her personality: the warm-bosomed earth mother; the whip-cracking CEO of her own company. As many have learnt to their cost in the past, woe betide any roadie that starts to slack on the job, for they will come up against the Wrath of Tori.

"Yeah, they are somewhat of an extended family," she notes, "but sometimes they don't know the line. Y'know, sometimes we're in the middle of a show and it's like, 'Whatever you all are talking about on the side of the stage, what are you doing?' And if they think, 'Oh, but that's my buddy Tori and I was just having a chat with my mate . . .' then you're gonna run into Tori Amos real quick. And she's a lioness. And you know what she doesn't like? If you take it for granted and piss on our friendship. And they'll say, 'But we're friends.' And I say, (coolly) 'Well, we still might be.'

"In a way," she concludes, "that's where you kind of have to go, 'Look guys, I love you, but I have to clean my daughter's runny bottom. I can't clean a 40 year old's, too. And play the piano . . .'"

Sure enough, it sounds like a tough job. But, you suspect, she'll manage somehow.

|